Gold, Mining, Collaboration and the End of Ethics

Why has collaboration been so widely celebrated as positive within workplaces? Shouldn't collaboration come with warnings attached, like how to avoid groupthink? Why does working alone often come with stigma and colleagues get shunned? I've written before about the evils of Public Private Philanthropic Partnerships (PPPPs), for example here:

...but it's not only these kinds of collaborations that have led to the demise of ethical policies in our public institutions, commercial organisations and arguably, society more widely. Where are the ethics?

Precious metals are front-of-mind for many of us at the moment, markets here in NZ and overseas are under close scrutiny. But just as many of us are now familiar with the World Health Organization's capture by BigPharma and its inevitable lack of ethics, could the World Gold Council also be under the microscope?

Recent subscribers may not have seen this article I published this time last year, after a visit to our local (historic) gold-mining town, Waihi:

In that article, I raise concerns of the lack of ethics in addressing the needs of those citizens impacted everyday by the commercial operations of that gold mine and its expansion. The small community's protests continue, and meanwhile, what has the global stakeholder entity that oversees gold-mining been doing?

In 2019 (coincidence?), we launched the Responsible Gold Mining Principles (RGMPs), a framework that sets out clear expectations for consumers, investors, and the gold supply chain as to what constitutes responsible gold mining. The RGMPs are intended to recognise and consolidate existing standards and instruments under a single framework. A number of leading standards already exist that address specific aspects of responsible gold mining, including the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct, and the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative . However, prior to the development of the RGMPs, there was no single coherent framework that addressed all aspects of responsible gold mining. During the development of the Responsible Gold Mining Principles, we undertook extensive external consultation with a broad range of stakeholders globally. [SOURCE]

And who ARE their stakeholders? Well, I think we can guess. Yes, it's the 30 largest gold-mining companies of the world:

So the markets that are controlling the mining and supply-chains of gold, are managed and controlled by the entities profiting from the mining of that gold. Including the 'ethical principles' that govern their policies. Makes perfect sense!

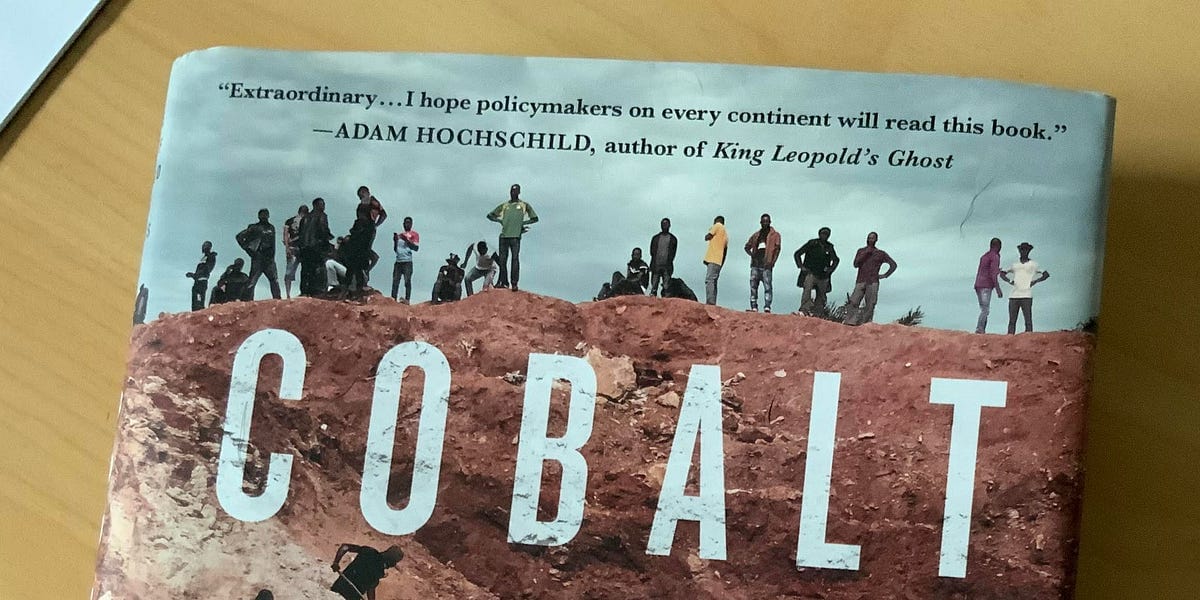

This situation reminds my of Prof Siddarth Kara's research into Modern Slavery, and again a post that recent subscribers may have missed was my review of his excellent expose, Cobalt Red:

Kara undertook some dangerous fieldwork in Africa, which confirmed his worst fears. The ethical policies supposed to prevent the suffering of children and vulnerable adults living in and near the lithium and cobalt mines, have failed. And reflecting the fake-gold-mining 'ethical guidelines', the cobalt and lithium that goes into the 'green' batteries are often sourced from operations that are the opposite from the ethical, sustainable image seen in the propaganda. In fact, just like The Gold Council, The Battery Council is also headed-up by the (mainly Chinese) mining companies that Kara exposes for numerous, appalling Human Rights abuses that continue everyday.

Collaboration, willful blindness and ethics

And this brings me to the purpose of this article: the word 'collaboration'. One of my colleagues kindly sent me a link to this fascinating talk from an Australian Professor of Ethics, Simon Longstaff, Director (and funder) of the NGO The Ethics Centre. This the summary and link to the talk (40m) which I highly recommend you take the time to hear:

At face value, collaboration sounds like a good thing: collaboration in the classroom, with colleagues, or between nations. But throughout history, collaboration was not always considered a virtuous act, and those who were identified as collaborators were shunned, humiliated or worse. This talk explores how people justify their involvement in wrongdoing, and how, when collaboration devolves into conformity, it risks silencing dissent.

How DO people justify their wrongdoing? It is more than groupthink and willful blindness. As I have explained previously, behavioural science has been weaponised against us. [eg see MINDSPACE: evidence of how global Nudge Units weaponised behavioural science against New Zealanders] In 'normal' circumstances, you would assume that an 'independent' entity like The Ethics Centre, self-declaring it's ambition to become the go-to national centre for everything ethics, would be aware of the dangers of propaganda. But apparently not. Back in March 2020, Prof Longstaff wrote this in the context of his hope that his Government would save us all from that 'deadly' infection:

Given the finite number of beds in intensive care units, respirators, etc. in Australia, the harsh truth is that if there is mass contagion, giving rise to critical illness on a broad scale, there will not be enough medical resources to sustain the lives of all who need care.

In those circumstances, medical staff and families will need to exercise triage – put simply, the practice of prioritising access to scarce medical resources. Not everyone will be chosen. Some of those at the end of the line will die. This is the harsh reality behind abstract talk of ‘flattening the curve’. [SOURCE]

I wonder what he thinks now of the flawed data and lack of ethics of that statement? BiologyPhenom, who continues to work hard on raising awareness of the evidence from the covid inquiries of the use and abuse of the end-of-life pathways during the covid era, would be appalled. And needless to say, as Robyn and I confirmed last week during our conversation [here: Interview with Robyn of Relentless - Courage is the Cure: Is Academia Broken?] so many of these incidents of fear-mongering propaganda by those 'experts' have been memory-holed. But Mistakes Were Not Made and we will never forget.

At the very end of his talk, Prof Longstaff was asked by an audience member about the dangers of collaboration and groupthink that lead people to now doubt 'expert' opinions. [how dare they!] Yet crucially, he did not expand upon the important reasons why there has been a collapse in public trust. Could it, Prof Longstaff, be caused by those same 'experts', now captured through, ironically, collaboration? Collaborations like The Ethics Centre itself?

Whether it's health, education, housing, mining for gold or materials for batteries, ethics seems absent from so much of our modern 'Big' society. As we keep saying, it's down to us, on the ground level, to recapture our own values, to clarify our moral compass, and to help each other to speak up in support of strong ethical principles.